Twenty Gallons Commissioned by LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions)

16 June 2011-25 March 2012

While Margie Livingston’s work could be easily and appropriately discussed as an art historical project that embraces the gestural hallmarks of Abstract Expressionism while simultaneously revealing the constructed nature of the “anarchic” and “spontaneous” mark making of late Modernist painting, our understanding of her practice might be better served by locating it within a more complex state of liminality. A term used to describe psychological or metaphysical states of hovering “in between” situations characterized by the dislocation of established systems and hierarchies, as a concept liminality proves to be useful when studying the dissolution of order as a means toward developing new structures, forms, and narratives.

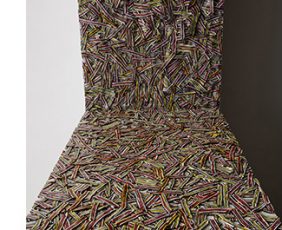

Twenty Gallons is a large scale, site specific installation commissioned by LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions) where Livingston covered the monumental 15-foot tall archway in LACE’s front gallery with a series of panels constructed entirely from, as her title suggests, twenty gallons of acrylic paint. The installation exists (deliberately so) within multiple overlapping and potentially conflicting contexts. While references to both the earnestness of Jackson Pollack’s manic gesturing and Roy Lichstenstein’s playful yet cooly calculated Three Brushstrokes are in abundance, arguable the most intriguing element of the installation its location, both literally and metaphorically; Twenty Gallons exists as a threshold between physical spaces and artistic disciplines.

Livingston still utilizes acrylic paint as a primary sculptural material in the same manner that has come to define her more recent work, yet the playfulness of the candy-like surface and color palette are upset by the impossibility of experiencing the work as a cohesive and unified whole. Her previous “paint-objects” tended to be singular objects which could be understood much like a painting or plinth mounted sculpture. Twenty Gallons is an installation that asks the audience to consider it as both of those things yet neither simultaneously. The scale and narrow dimensions of the work make it difficult to inhabit as a traditional installation; when one views the work from a distance, the work becomes distorted and difficult to comprehend, yet upon entering the work it flattens itself out and becomes an overwhelming panorama of mimicry and signification. Paint has been poured and treated like sculptural material which in turn has been formed to resemble “expressive” brush strokes, then layered to suggest particle board or some other architectural or sculptural material.

Livingston’s work is necessarily ambiguous at the moment as it is suggestive of the artist moving away from a material critique of late modernism towards a more complex and open ended investigation of the slippages that are produced within the shifting relationships between material, location, and scale.

— Robert Crouch

Bio

Robert Crouch is a Los Angeles based artist and curator. He has performed, exhibited, and curated projects at venues including The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, The Hammer Museum, and The de Young Museum. He is currently the Associate Director/Curator at LACE and the Director of VOLUME.

Support

Support for Livingston’s residency to create Twenty Gallons has been generously provided by the Visual Artists Network, a program of the National Performance Network, whose major contributors are the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the Joan Mitchell Foundation, and the Nathan Cummings Foundation.

Additional support for LACE and its programs is provided by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, the Getty Foundation, Jerry and Terri Kohl Family Foundation, Los Angeles County Arts Commission, The Mohn Family Foundation, Morris Family Foundation, the Audrey & Sydney Irmas Charitable Foundation, National Performance Network, the C. Christine Nichols Donor Advised Fund at the Community Foundation of Abilene, Stone Brewing Co., and the members of LACE.

Room

2009

Acrylic and adhesive

Installation view, as part of Expo at SOIL

In 2009, I accepted the challenge of creating new work in an unfamiliar medium. The venue was Expo, a show by the members of SOIL, Seattle’s artist-run gallery for developing, exhibiting, and advancing experimental and innovative art. The assignment I gave myself for Expo was to use paint as a sculptural medium.

It’s not that sculpture was completely new to me. It has been my practice for a long time to clarify my ideas about light, form, and space by building objects as models for my paintings. Although the paintings that emerge from this practice may look like abstractions, they are actually concerned with the same phenomena elucidated by the models. But, facing the Expo challenge, I found myself becoming curious about the influences that painting could have on the way I build things. And so, in a reversal of my usual process, I began using paint to construct objects.

The piece I made for Expo was called Room. It consisted of a single continuous row of paint drops lined up at eye level all the way around the gallery’s walls and front window. This two-dimensional painting had the effect of turning the gallery itself into a painting that the viewer could enter as a three-dimensional space. It became the first major piece in a new body of work that teases out and holds the tension between actual space and an illusion of space.

Commissioned by Seattle City Light 1% for Art Portable Works Collection As Part of the Elevator Lobbies Project

Best Sunny Day

Daylight with Red and Yellow Gels

Daylight with White Spotlight

Dark with Blue Spotlight

2008

Oil on linen

60 x 44 inches each

Livingston has created four related but unique experiences of color, light, and space, bridging the gap between abstraction and representation. The source for all the paintings is the same—a 6’ x 6’ x 6’ grid of string she built in her studio.

The structure references the grid of modernism, the grid of architecture, the grid of linear perspective developed in the Renaissance, as well as the wire frame of contemporary 3-D computer illustration.

Each painting takes a specific point of view with a unique combination of warm and cool lights while playing with the tension between things falling apart and coming together. Livingston hopes “as people live with the work, they will find connections that deepen their experience of each part in relation to the whole.”